Throughout my career, I occasionally ran up against people who were more than willing to volunteer as interpreters for Black people, as in

“What Vera is trying to say is . . . .”

This always struck me as a rude putdown. Just let Vera speak for herself, I thought. As often as not, the “interpreters” were only pushing her aside to make whatever point they wanted to make.

For most of history, that’s what has happened to Black Americans, especially in books, movies, and television programs. With a scarcity of Black voices like James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, and Spike Lee, white writers and directors from the earliest media productions took it upon themselves to represent Black people, who usually were portrayed as childlike at best and ignorant or malicious at worst.

Like many white people of my generation, books, movies, and TV shaped my limited understanding of Black Americans. As a boy, I devoured episode after episode of Our Gang comedies, repackaged as The Little Rascals for my generation, the first TV generation. The series, produced from 1922 to 1944, presented the adventures of poor neighborhood children with a mixed bag of racial messages. The Black kids — Farina (Allen Hoskins), Stymie (Matthew Beard), and Buckwheat (Billie Thomas) — suffered their share of racial stereotyping. They spoke in exaggerated dialects, resurrected decades later by Eddie Murphy as he spoofed Buckwheat on Saturday Night Live. Still, I saw Black children treated as equals by their white playmates, which rarely happened in real life. I came away thinking any of them would be fun to have as friends.

But some white people saw even this meager integration as a threat. During the heyday of Our Gang, a number of theater owners in southern states complained that the Black children got too much screen time. They thought the children’s prominence might offend white audiences. If I had known this as a boy, I would have thought it was crazy. It took a movie far different from The Little Rascals to rattle me and expose how far I needed to go on issues of race and racism.

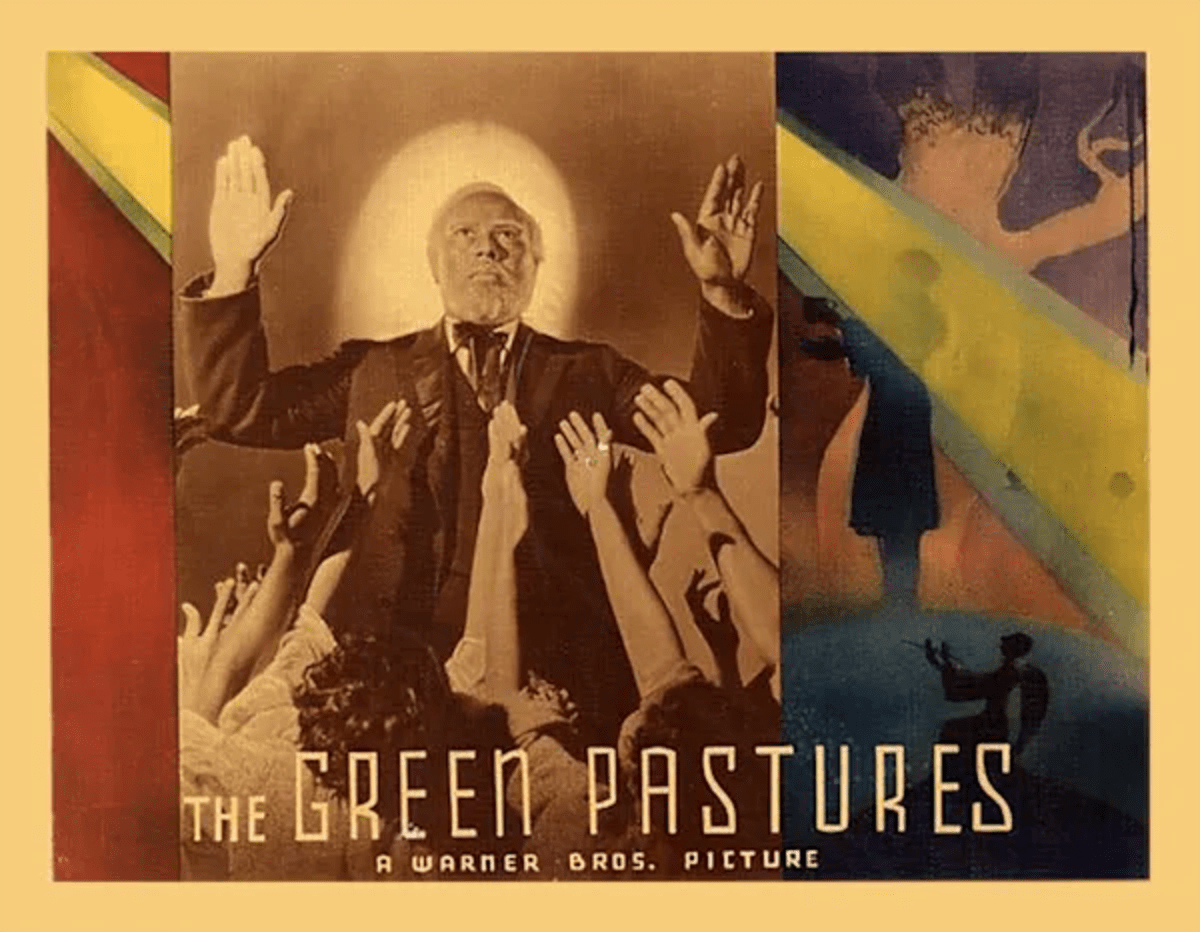

During one summer vacation, when I was ten or eleven, I flipped through St. Louis’s five TV channels and stumbled upon the movie The Green Pastures. The film, released in 1936, featured an all-Black cast. It’s adapted from Marc Connelly’s play of the same name, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1930. I doubt many in the Black community or elsewhere would applaud it today.

In 1936, The Pittsburgh Press said this about the Connelly’s motives:

“The entire cast of the film now in production is composed, of course, of colored folk, recruited from New York and Los Angeles’ own Little Harlem. And there’s the rub. Pittsburgh’s Marc Connelly, who dramatized the fable (on stage) in black face, is directing it.“To his dismay his colored folk couldn’t talk like southern Negroes — so he has hired a coach, a young white actor, William Austin, who is from Louisiana. Mr. Austin is teaching the Negroes to talk like Negroes.” ~ The Pittsburgh Press, February 3, 1936, page 18.

In other words, Connelly was going to make his actors conform to his image of what Black people should be, even though they weren’t actually anything like he had in mind. I don’t think The Green Pastures was meant to be malicious, but it’s a product of its time, written by a white man and filled with stereotyping that is inappropriate.

As soon as I started watching, the movie disturbed me. It portrays both heaven and Old Testament stories as seen through the eyes of a young African-American girl in the Depression-era South. Here was a Black God portrayed by Rex Ingram, whose commanding presence and powerful voice made him a natural for the part. All the other Bible characters, Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and the angel Gabriel, were Black. I had a meltdown so severe that I ran to the kitchen to drag my mother back to the TV screen.

“What is this?” I asked her. “This isn’t right!” I can’t recall what she had to say other than telling me to turn it off if it bothered me so much.

I’m the product of Missouri Synod Lutheran schools, which have always prided themselves on “pure doctrine.” I left that church body nearly thirty years ago, but it certainly had a grip on me as a boy. The Germans who founded and controlled the school system had definite ideas about the Bible and the heroes of faith, whether BCE or CE. Or, as I imagine they prefer even now, whether BC or AD.

In the Bible storybooks we used in school, Adam was white. Eve was white. Moses was white. David was white. Daniel was white. Jesus was white. All God’s children were white, even though they weren’t! All God’s children spoke King James English, too. And so it seemed to me that The Green Pastures was sacrilegious. Blasphemous, even. Beyond that, some characters smoked cigars and carried guns, and those anachronisms confused me even more.

The music also bothered me. For a kid raised on hymns like A Mighty Fortress and Silent Night, the lively spirituals seemed too raucous to be served up to the Lord.

As I’ve aged, I’ve thought about why I had such a visceral reaction to The Green Pastures. A lot of that response came from my narrow, rigid, white Christian tradition. As a friend sometimes tells me, that upbringing left me with a broomstick up my ass that’s never been totally dislodged. I’ve made some progress. Today, I’d much rather listen to gospel music than many of the dirge-like Reformation hymns, and I’ve come to see the power and beauty of statements of faith like James Weldon Johnson’s poem, The Creation.

There was something more deeply rooted within me, I think. As I looked at all those Black people, it disturbed me that I wasn’t represented among them. There was no place for me in the heaven I was seeing. My kind and I were excluded — invisible — and I both feared and resented it.

In some small way, it’s given me a better understanding of what Black Americans have experienced for decade after decade, and what they often experience now. Black people were rarely seen in the entertainment of my boyhood, showing up only if and when white producers needed them to fill roles that white writers defined for them. And more consequentially day to day, in the real world, Black people were relegated to neighborhoods open to them only after whites abandoned them for, let’s say, greener pastures. It’s still often true today.

The outrage among Black people that being excluded can generate scares many white people, who don’t understand it. These white people think the outrage is unjustified as they point to civil-rights progress made over the past half century. Unspoken, I think, is the misguided notion that Black America should be grateful for what the legislatures and courts have done to make their lives better.

That’s not the issue, though. It’s not whether Black America has been “given” more. It’s that Black America is still not in equal partnership, not equally a force in the decision-making that determines their destiny and our destiny as a nation. It’s also that nothing seems to be done about injustices committed against the Trayvon Martins, the George Floyds, and the Breonna Taylors of the world. It’s that all too often, their concerns and their lives remain ignored.

Ralph Ellison, in his book Invisible Man, provided some insight into how Blackness often renders people invisible in America, but it took The Green Pastures for me to understand, just a little, the fear and resentment that Black people must feel from being routinely excluded and unrecognized.

(This article appeared originally on Our Human Family.)

Photo Information

A detail from the Warner Bros

poster promoting The Green Pastures